Arunachal Pradesh

| Arunachal Pradesh | |||

| — state — | |||

| |||

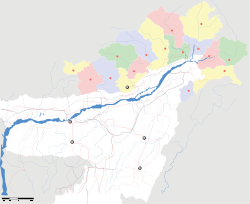

| Location of Arunachal Pradesh in India | |||

| Coordinates | 27.06°N 93.37°E / 27.06°N 93.37°E | ||

| Country | |||

| District(s) | 16 | ||

| Established | 20 February 1987 | ||

| Capital | Itanagar | ||

| Largest city | Itanagar | ||

| Governor | Joginder Jaswant Singh (2008-) | ||

| Chief Minister | Dorjee Khandu (2007-) | ||

| Legislature (seats) | Unicameral (60) | ||

| Population • Density | 1,091,120 (26th) • 13 /km2 (34 /sq mi) | ||

| HDI (2005) | 0.617 (medium) (18th) | ||

| Literacy | 62.8% (24th) | ||

| Official languages | Hindi, Deori, Assamese, English, and many local languages. | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Time zone | IST (UTC+5:30) | ||

| Area | 83743 km2 (32333 sq mi) | ||

| ISO 3166-2 | IN-AR | ||

| Website | arunachalpradesh.nic.in | ||

Arunachal Pradesh (Hindi: अरुणाचल प्रदेश, pronounced [ərʊˈɳaːtʃəl prəˈd̪eːʃ] (![]() listen)) is a state of India, located in the far northeast. It borders the states of Assam and Nagaland to the south, and shares international borders with Burma in the east, Bhutan in the west, and the People's Republic of China in the north. The majority of the territory is claimed by the People's Republic of China as part of South Tibet. The northern border of Arunachal Pradesh reflects the McMahon Line, a controversial 1914 treaty between the United Kingdom and a Tibetan government, which was never accepted by the Chinese government, and not enforced by the Indian government until 1950. Itanagar is the capital of the state.

listen)) is a state of India, located in the far northeast. It borders the states of Assam and Nagaland to the south, and shares international borders with Burma in the east, Bhutan in the west, and the People's Republic of China in the north. The majority of the territory is claimed by the People's Republic of China as part of South Tibet. The northern border of Arunachal Pradesh reflects the McMahon Line, a controversial 1914 treaty between the United Kingdom and a Tibetan government, which was never accepted by the Chinese government, and not enforced by the Indian government until 1950. Itanagar is the capital of the state.

Arunachal Pradesh means "land of the dawn lit mountains"[1] in Sanskrit. It is also known as "land of the rising sun"[2] ("pradesh" means "state" or "region") in reference to its position as the easternmost state of India. Most of the people native to and/or living in Arunachal Pradesh are of Tibeto-Burman origin. A large and increasing number of migrants have reached Arunachal Pradesh from many other parts of India, although no reliable population count of the migrant population has been conducted, and percentage estimates of total population accordingly vary widely. Part of the famous Ledo Burma Road, which was a lifeline to China during World War II, passes through the eastern part of the state.

Contents[hide] |

History

Early history

The history of pre-modern Arunachal Pradesh remains shrouded in mystery. It is popularly believed, and may be speculatively assumed, that the first ancestors of most indigenous tribal groups migrated from pre-Buddhist Tibet two or three thousand years ago, if not before, and were joined by Tibetic and Thai-Burmese counterparts later. The earliest written references to Arunachal are popularly believed to be found in the Mahabharata, Ramayana and other Vedic legends. Several characters, such as, King Bhismaka, are believed to represent people from the region in the Mahabharata; however, since corroborating information is unavailable, and since place-names cannot be verified at that historical time-depth, such associations are to a large extent speculative. For example, there is no evidence whatsoever that the name Bhismaka plausibly associates with any indigenous Arunachali tribes or languages at all.

Oral histories possessed to this day by many Arunachali tribes of Tibeto-Burman stock are much richer, and point unambiguously to a northern origin in modern-day Tibet. Again, however, corroboration remains difficult. From the point of view of material culture, it is clear that most indigenous Arunachali groups align with Burma-area hill tribals, a fact that could either be explainable in terms of a northern Burmese origin or from westward cultural diffusion.

From the perspective of material culture, the most unusual Arunachali group by far is the Puroik/Sulung, whose traditional staple food is sago palm and whose primary traditional productive strategy is foraging. While speculatively considered to be a Tibeto-Burman population, the uniqueness of Puroik culture and language may well represent a tenuous reflection of a distant and all but unknown pre-Tibeto-Burman, Tai and Indo-Aryan past.

Recorded history from an outside perspective only became available in the Ahom chronicles of the 16th century. The Monpa and Sherdukpen do keep historical records of the existence of local chiefdoms in the northwest as well. Northwestern parts of this area came under the control of the Monpa kingdom of Monyul, which flourished between 500 B.C. and 600 A.D. This region then came under the loose control of Tibet and Bhutan, especially in the Northern areas. The remaining parts of the state, especially those bordering Myanmar, came under the titular control of the Ahom and the Assamese until the annexation of India by the British in 1858. However, most Arunachali tribes remained in practice largely autonomous up until Indian independence and the formalization of indigenous administration in 1947.

Recent excavations of ruins of Hindu temples such as the 14th century Malinithan at the foot of the Siang hills in West Siang are somewhat automatically associated with the ancient history of Arunachal Pradesh, inasmuch as they fall within its modern-day political borders. However, such temples are generally south-facing, never occur more than a few kilometers from the Assam plains area, and are perhaps more likely to have been associated with Assam plains-based rather than indigenous Arunachali populations. Another notable heritage site, Bhismaknagar, has led to suggestions that the Idu (Mishmi) had an advanced culture and administration in pre-historical times. Again, however, no evidence directly associates Bhismaknagar with this or any other known culture. The third heritage site, the 400-year-old Tawang Monastery in the extreme north-west of the state, provides some historical evidence of the Buddhist tribal peoples. Historically, the area had a close relationship with Tibetan people and Tibetan culture, for example the sixth Dalai Lama Tsangyang Gyatso was born in Tawang.[3]

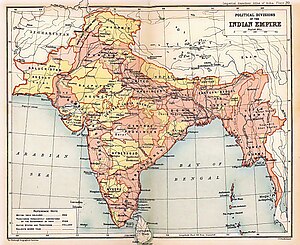

Drawing of McMahon line

In 1913-1914 representatives of China, Tibet and Britain negotiated a treaty in India: the Simla Accord.[4] This treaty's objective was to define the borders between Inner and Outer Tibet as well as between Outer Tibet and British India. British administrator, Sir Henry McMahon, drew up the 550 miles (890 km) McMahon Line as the border between British India and Outer Tibet during the Simla Conference. The Tibetan and British representatives at the conference agreed to the line, which ceded Tawang and other Tibetan areas to the British Empire. The Chinese representative had no problems with the border between British India and Outer Tibet, however on the issue of the border between Outer Tibet and Inner Tibet the talks broke down. Thus, the Chinese representative refused to accept the agreement and walked out.[citation needed] The Tibetan Government and British Government went ahead with the Simla Agreement and declared that the benefits of other articles of this treaty would not be bestowed on China as long as it stays out of the purview.[5] The Chinese position was that Tibet was not independent from China, so Tibet could not have independently signed treaties, and per the Anglo-Chinese (1906) and Anglo-Russian (1907) conventions, any such agreement was invalid without Chinese assent.[6]

Simla was initially rejected by the Government of India as incompatible with the 1907 Anglo-Russian Convention. However, this agreement(Anglo-Russian Convention) was renounced by Russia and Britain jointly in 1921, thus making the Simla Conference official.[citation needed] However, with the collapse of Chinese power in Tibet the line had no serious challenges as Tibet had signed the convention, therefore it was forgotten to the extent that no new maps were published until 1935, when interest was revived by civil service officer Olaf Caroe. The Survey of India published a map showing the McMahon Line as the official boundary in 1937.[citation needed] In 1938, the British finally published the Simla Convention as a bilateral accord two decades after the Simla Conference; in 1938 the Survey of India published a detailed map showing Tawang as part of NEFA. In 1944 Britain established administrations in the area, from Dirang Dzong in the west to Walong in the east. Tibet, however, altered its position on the McMahon Line in late 1947 when the Tibetan government wrote a note presented to the newly independent Indian Ministry of External Affairs laying claims to the Tibetan district (Tawang) south of the McMahon Line.[7] The situation developed further as India became independent and the People's Republic of China was established in 1949. With the PRC poised to take over Tibet, India unilaterally declared the McMahon Line to be the boundary in November 1950, and forced the last remnants of Tibetan administration out of the Tawang area in 1951.[8][9] The PRC has never recognized the McMahon Line, and claims Tawang on behalf of Tibetans.[10] The 14th Dalai Lama, who led the Tibetan government from 1950 to 1959, said as recently as 2003 that Tawang is "actually part of Tibet".[11] He reversed his position in 2008, saying that it was part of India.[11]

Conflicts between China and India

The NEFA (North East Frontier Agency) was created in 1954. The issue was quiet during the next decade or so of cordial Sino-Indian relations, but erupted again during the Sino-Indian War of 1962. The cause of the escalation into war is still disputed by both Chinese and Indian sources. During the war in 1962, the PRC captured most area of Arunachal Pradesh. However, China soon declared victory, voluntarily withdrew back to the McMahon Line and returned Indian prisoners of war in 1963. The war has resulted in the termination of barter trade with Tibet, although in 2007 the state government has shown signs to resume barter trade with Tibet.[12]

After the war

Arunachal Pradesh became a separate state of India in 1986.

Of late, Arunachal Pradesh has come to face threats from certain insurgent groups, notably the National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN), who are believed to have base camps in the districts of Changlang and Tirap.[13] There are occasional reports of these groups harassing local people and extracting protection money.[14]

Geography

Much of Arunachal Pradesh is covered by the Himalayas. However, parts of Lohit, Changlang and Tirap are covered by the Patkai hills. Kangto, Nyegi Kangsang, the main Gorichen peak and the Eastern Gorichen peak are some of the highest peaks in this region of the Himalayas.

At the lowest elevations, essentially at Arunachal Pradesh's border with Assam, are Brahmaputra Valley semi-evergreen forests. Much of the state, including the Himalayan foothills and the Patkai hills, are home to Eastern Himalayan broadleaf forests. Toward the northern border with China, with increasing elevation, come a mixture of Eastern and Northeastern Himalayan subalpine conifer forests followed by Eastern Himalayan alpine shrub and meadows and ultimately rock and ice on the highest peaks.

In 2006 Bumla pass in Tawang was opened to traders for the first time in 44 years. Traders from both sides of the pass were permitted to enter each other's territories, in addition to postal workers from each country.

The Himalayan ranges that extend up to the eastern Arunachal separate it from Tibet. The ranges extend toward Nagaland, and form a boundary between India and Burma in Changlang and Tirap district, acting as a natural barrier called Patkai Bum Hills. They are low mountains compared to the Greater Himalayas.[15]

Climate

The climate of Arunachal Pradesh varies with elevation. Areas that are at a very high elevation in the Upper Himalayas close to the Tibetan border enjoy an alpine or Tundra climate. Below the Upper Himalayas are the Middle Himalayas, where people experience a temperate climate. Areas at the sub-Himalayan and sea-level elevation generally experience humid, sub-tropical climate with hot summers and mild winters.

Arunachal Pradesh receives heavy rainfall of 80 to 160 inches (2,000 to 4,100 mm) annually, most of it between May and September. The mountain slopes and hills are covered with alpine, temperate, and subtropical forests of dwarf rhododendron, oak, pine, maple, fir, and juniper; sal (Shorea) and teak are the main economically valuable species.

Sub-divisions

Arunachal Pradesh is divided into sixteen districts, each administered by a district collector, who sees to the needs of the local people. Especially along the Tibetan border, the Indian army has a considerable presence due to concerns about Chinese intentions in the region. Special permits called Inner Line Permits (ILP) are required to enter Arunachal Pradesh through any of its checkgates on the border with Assam.

Districts of Arunachal Pradesh:

Economy

The chart below displays the trend of the gross state domestic product of Arunachal Pradesh at market prices estimated

| Year | Gross State Domestic Product |

|---|---|

| 1980 | 1,070 |

| 1985 | 2,690 |

| 1990 | 5,080 |

| 1995 | 11,840 |

| 2000 | 17,830 |

Arunachal Pradesh's gross state domestic product for 2004 was estimated at $706 million in current prices. Agriculture primarily drives the economy. Jhum, the local word for a shifting cultivation widely practiced among the tribal groups, is now less practiced. Arunachal Pradesh has close to 61,000 square kilometers of forests, and forest products are the next most significant sector of the economy. Among the crops grown here are rice, maize, millet, wheat, pulses, sugarcane, ginger, and oilseeds. Arunachal is also ideal for horticulture and fruit orchards. Its major industries are rice mills, fruit preservation units, and handloom handicrafts. Sawmills and plywood trades are prohibited under law.[16]

Arunachal Pradesh accounts for a large percentage of India's untapped hydroelectric power production potential. In 2008, the state government of Arunachal Pradesh signed deals with various Indian companies planning some 42 hydroelectric schemes that will produce electricity in excess of 27,000 MW.[17] Construction of the Upper Siang Hydroelectric Project, which is expected to generate between 10,000 to 12,000 MW, began in April 2009.[18]

Corruption in Arunachal Pradesh is endemic, and reputed to be among the worst in India. During 2009 elections, the Arunachal Times reported that virtually all of the leading candidates had reported personal fortunes to the equivalent of several million US dollars - in a state with no income tax and where the average per capita income is only a dollar or two per day. The failure of Arunachali people to hold their leaders accountable has led to tremendous drains on the economy and a crumbling infrastructure.

Another missed economic opportunity is that of tourism. Boasting a scenic natural beauty that equals and in some respects surpasses that of other Himalayan regions such as Sikkim, Bhutan, and Nepal, Arunachal Pradesh's strict and expensive "Restricted/Protected Area Permit" scheme ensures both that no more than a trickle of foreign tourists are able to visit the state each year, and that revenues so obtained go directly into the pockets of government officials and affiliated tour operators. Little if any benefit from tourism is able to reach the general population, which remains in general relatively impoverished.

Languages

Modern-day Arunachal Pradesh is one of the linguistically richest and most diverse regions in all of Asia, being home to at least thirty and possibly as many as fifty distinct languages in addition to innumerable dialects and subdialects thereof. Boundaries between languages very often correlate with tribal divisions - for example, Apatani and Nyishi are both tribally and linguistically distinct - but shifts in tribal identity and alignment over time have also ensured that a certain amount of complication enters into the picture - for example, Galo is and has seemingly always been linguistically distinct from Adi, whereas the earlier tribal alignment of Galo with Adi (i.e., "Adi Gallong") has only recently been essentially dissolved.

The vast majority of languages indigenous to modern-day Arunachal Pradesh belong to the Tibeto-Burman language family. The majority of these in turn belong to a single branch of Tibeto-Burman, namely Tani. Almost all Tani languages are indigenous to central Arunachal Pradesh, including (moving from west to east) Nyishi/Nishi, Apatani, Bangni, Tagin, Hills Miri, Galo, Bokar, Lower Adi (Padam, Pasi, Minyong, and Komkar), Upper Adi (Aashing, Shimong, Karko and Bori), and Milang; only Mising, among Tani languages, is primarily spoken outside Arunachal Pradesh in modern-day Assam, while a handful of northern Tani languages including Bangni and Bokar are also spoken in small numbers in Tibet. Tani languages are noticeably characterized by an overall relative uniformity, suggesting relatively recent origin and dispersal within their present-day area of concentration. Most Tani languages are mutually intelligible with at least one other Tani language, meaning that the area constitutes a dialect chain, as was once found in much of Europe; only Apatani and Milang stand out as relatively unusual in the Tani context. Tani languages are among the better-studied languages of the region.

To the east of the Tani area lie three virtually undescribed and highly endangered languages of the "Mishmi" group of Tibeto-Burman, Idu, Digaru and Miju. A certain number of speakers of these languages are also found in Tibet. The relationships of these languages, both amongst one another and to other area languages, are as yet uncertain. Further south, one finds the Singpho (Kachin) language, which is primarily spoken by large populations in Burma, and the Nocte and Wancho languages, which show affiliations to certain "Naga" languages spoken to the south in modern-day Nagaland.

To the west and north of the Tani area are found at least one and possibly as many as four Bodic languages, including Dakpa and Tshangla; within modern-day India, these languages go by the cognate but, in usage, distinct designations Monpa and Memba. Most speakers of these languages or closely related Bodic languages are found in neighbouring Bhutan and Tibet, and Monpa and Memba populations remain closely adjacent to these border regions.

Between the Bodic and Tani areas lie a large number of almost completely undescribed and unclassified languages, which, speculatively considered to be Tibeto-Burman, exhibit many unique structural and lexical properties that probably reflect both a long history in the region and a complex history of language contact with neighbouring populations. Among them are Sherdukpen, Bugun, Aka/Hruso, Koro, Miji, Bangru and Puroik/Sulung. The high linguistic significance of all of these languages is belied by the extreme paucity of documentation and description of them, even in view of their highly endangered status. Puroik, in particular, is perhaps one of the most culturally and linguistically unique and significant populations in all of Asia from proto-historical and anthropological-linguistic perspectives, and yet virtually no information of any real reliability regarding their culture or language can be found in print even to this day.

Finally, there is an unknown number of Tibeto-Burman languages of Nepal-area origin spoken in modern-day Arunachal Pradesh, including Gurung and Tamang; not classified as "tribal" in the Arunachali context, such languages generally go unrecognized, while their speakers are largely viewed as itinerant "Nepalis". An unknown number of Tibetan dialects are similarly spoken by recent migrants from Tibet, although they are not generally recognized or classified as tribal or indigenous.

Outside of Tibeto-Burman, one finds in Arunachal Pradesh a single representative of the Tai language family, namely the Khamti language, which is closely affiliated to the Shan dialects of northern Burma; seemingly, Khamti is a recent arrival in Arunachal Pradesh whose presence dates from 18th and/or early 19th-century migrations from northern Burma. In addition to these non-Indo-European languages, the Indo-European languages Assamese, Bengali, English, Nepali and especially Hindi are making strong inroads into Arunachal Pradesh. Primarily as a result of the primary education system - in which classes are generally taught by Hindi-speaking immigrant teachers from Bihar and other Hindi-speaking parts of northern India - a large and growing section of the population now speaks a semi-creolized variety of Hindi as its mother tongue.

Demographics

| [show]Population Growth |

|---|

Arunachal Pradesh can be roughly divided into a set of semi-distinct cultural spheres, on the basis of tribal identity, language, religion, and material culture: the Tibetic area bordering Bhutan in the west, the Tani area in the centre of the state, the Mishmi area to the east of the Tani area, the Tai/Singpho/Tangsa area bordering Burma, and the "Naga" area to the south, which also borders Burma. In between there are transition zones, such as the Aka/Hruso/Miji/Sherdukpen area, which provides a "buffer" of sorts between the Tibetic Buddhist tribes and the animist Tani hill tribes. In addition, there are isolated peoples scattered throughout the state, such as the Sulung.

Within each of these cultural spheres, one finds populations of related tribes speaking related languages and sharing similar traditions. In the Tibetic area, one finds large numbers of Monpa tribespeople, with several subtribes speaking closely related but mutually incomprehensible languages, and also large numbers of Tibetan refugees. Within the Tani area, major tribes include Nishi, which has recently come to be used by many people to encompass Bangni, Tagin and even Hills Miri. Apatani also live among the Nishi, but are distinct. In the centre, one finds predominantly Galo people, with the major sub-groups of Lare and Pugo among others, extending to the Ramo and Pailibo areas (which are close in many ways to Galo). In the east, one finds the Adi, with many subtribes including Padam, Pasi, Minyong, and Bokar, among others. Milang, while also falling within the general "Adi" sphere, are in many ways quite distinct. Moving east, the Idu, Miju and Digaru make up the "Mishmi" cultural-linguistic area, which may or may not form a coherent historical grouping.

Moving southeast, the Tai Khamti are linguistically distinct from their neighbours and culturally distinct from the majority of other Arunachali tribes;They are religiously similar to the Chakmas who have migrated from erstwhile East Pakistan.They follow the same Theraveda sect of Buddhism.The Chakmas consist of the majority of the tribal population.Districts of Lohit,Changlang,Dibang and Papumpare have a considerable number of Chakmas. They speak a linguistic variant derived from Assamese and Bengali. Their language is more similar to Assamese . Assam also have a large population of Chakmas who reside in the district of Karbi Anglong , Nagaon and Kachar. however, they also exhibit considerable convergence with the Singpho and Tangsa tribes of the same area; all of these groups are also found in Burma. Finally, the Nocte and Wancho exhibit cultural and possibly also linguistic affinities to the tribes of Nagaland, which they border.

In addition, there are large numbers of migrants from diverse areas of India and Bangladesh, who, while legally not entitled to settle permanently, in practice stay indefinitely, progressively altering the traditional demographic makeup of the state. Finally, populations of "Nepalis" (in fact, usually Tibeto-Burman tribespeople whose tribes predominate in areas of Nepal, but who do not have tribal status in India) and Chakmas are distributed in different areas of the state (although reliable figures are hard to come by).

Literacy has risen in official figures to 54.74% from 41.59% in 1991. The literate population is said to number 487,796.

An uncertain but relatively large percentage of Arunachal's population are animist, and follow shamanistic-animistic religious traditions such as Donyi-Polo (in the Tani area) and Rangfrah (further east). A small number of Arunachali peoples have traditionally identified as Hindus, although the number is growing as animist traditions are merged with Hindu traditions. Tibetan Buddhism predominates in the districts of Tawang, West Kameng, and isolated regions adjacent to Tibet. Theravada Buddhism is practiced by groups living near the Burmese border. Around 19% of the population are said to be followers of the Christian faith,[20] and this percentage is probably growing due to Christian missionary activities in the area.

A law has been enacted to protect the indigenous religions (e.g., Donyi-Poloism, Buddhism) in Arunanchal Pradesh against the spread of other religions, though no comparable law exists to protect the other religions.

Transport

The state's airports are located at Daparjio, Ziro, Along, Tezu and Pasighat. However, owing to the rough terrain, these airports are mostly small and cannot handle many flights. Before being connected by road, they were originally used for the transportation of food.

Arunachal Pradesh has two highways: the 336 km (209 mi) National Highway 52, completed in 1998, which connects Jonai with Dirak,[21] and another highway, which connects Tezpur in Assam with Tawang.[22] As of 2007, every village has been connected by road thanks to funding provided by the central government. Every small town has its own bus station and daily bus services are available. All places are connected to Assam, which has increased trading activity. An additional National Highway is being constructed following the famous Stillwell Ledo Road, which connects Ledo in Assam to Jairampur in Arunachal.

Education

The current education system in Arunachal Pradesh is relatively underdeveloped. The state government is expanding the education system in concert with various NGOs like Vivekananda Kendra.

The state has several reputable schools, colleges, and institutions. There are also trust institutes like Pali Vidyapith run by Buddhists. They teach Pali and Khamti scripts in addition to typical educational subjects. Khamti is the only tribe in Arunachal Pradesh that has its own script. Libraries of sciptures are located in a number of places in Lohit district, the largest one in Chowkham.

Rajiv Gandhi University is the premier educational institution, the only university in the entire state. Additionally, there are 7 government colleges in different districts, providing students a higher education. NERIST (North Eastern Regional Institute of Science and Technology) plays an important role in technical and management higher education. The directorate of technical education conducts examinations yearly, so that students who qualify can continue on to higher studies in other states.

The state has two polytechnic institutions, namely Rajiv Gandhi Govt. Polytechnic, located at Itanagar, and Tomi Polytechnic College, located at Basar.

| Sl. No. | Name of Colleges | Location | Year of establishment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rajiv Gandhi Govt. Polytechnic | Itanagar | 2002 |

| 2 | Tomi Polytechnic College | Basar | 2006 |

Tourism

Arunachal Pradesh attracts tourists from many parts of the world. Tourist attractions include Tawang, a beautiful town famous for its Buddhist monastery, Ziro, famous for cultural festivals, the Namdapha tiger project in Changlang district and Sela lake near Bomdila with its bamboo bridges overhanging the river. Religious places of interest include Malinithan in Lekhabali, Rukhmininagar near Roing (the place where Rukmini, Lord Krishna's wife in Hindu mythology, is said to have lived), and Parshuram Kund in Lohit district (which is believed to be the lake where Parshuram washed away his sins). Rafting and trekking are common activities. A visitor's permit from the tourism department is required. Places like Tuting have wonderful, undiscovered scenic beauty.

State Symbols

| State Bird | State Flower | State Animal | State Tree |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hornbill | Foxtail Orchid | Hoolock gibbon | Hollong |

See also

Notes

- ^ Usha Sharma (2005). Discovery of North-East India. Mittal Publications. p. 65. ISBN 9788183240345.

- ^ "Arunachal Pradesh - The Land of the Rising Sun". Indyahills.com. http://www.indyahills.com/arnp/. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ^ 仓央嘉措生平疏议(Biography of Cangyang Gyaco; in Chinese)

- ^ "Simla Convention". Tibetjustice.org. http://tibetjustice.org/materials/treaties/treaties16.html. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ^ Lamb, Alastair, The McMahon line: a study in the relations between India, China and Tibet, 1904 to 1914, London, 1966, p529

- ^ Ray, Jayanta Kumar (2007). Aspects of India's International relations, 1700 to 2000: South Asia and the World. History of science, philosophy, and culture in Indian civilization: Towards independence. Pearson PLC. p. 202. ISBN 9788131708347.

- ^ Lamb, 1966, p580

- ^ "The battle for the border". Rediff.com. 2003-06-23. http://www.rediff.com/news/2003/jun/21spec.htm. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ^ India’s China War by Neville Maxwell[dead link]

- ^ Ramachandran, Sudha (2008-06-27). "China toys with India's border". South Asia (Asia Times). http://www.atimes.com/atimes/South_Asia/JF27Df01.html. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

- ^ a b "Tawang is part of India: Dalai Lama". TNN. 4 June 2008. http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/India/Tawang_is_part_of_India_Dalai_Lama_/articleshow/3097568.cms. Retrieved 4 June 2008.

- ^ PM to visit Arunachal in mid-Feb[dead link]

- ^ "Apang rules out Chakma compromise". Telegraphindia.com. 2003-08-12. http://www.telegraphindia.com/1030812/asp/northeast/story_2255514.asp. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "Trekking in Arunachal, Trekking Tour in Arunachal Pradesh,Adventure Trekking in Arunachal Pradesh". North-east-india.com. http://www.north-east-india.com/arunachal-pradesh/trekking-arunachal.html. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ^ Arunachal Pradesh Economy, This Is My India

- ^ "Massive dam plans for Arunachal". Indiatogether.org. http://www.indiatogether.org/2008/feb/env-arunachal.htm. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ^ India pre-empts Chinese design in Arunachal

- ^ "Census Population"(PDF). Census of India. Ministry of Finance India. http://indiabudget.nic.in/es2006-07/chapt2007/tab97.pdf. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ "Census Reference Tables, C-Series Population by religious communities". Censusindia.gov.in. http://www.censusindia.gov.in/Census_Data_2001/Census_data_finder/C_Series/Population_by_religious_communities.htm. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ^ Oral Answers to Questions September 13, 1991, Parliament of India

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ "Web India". Webindia123.com. 2007-10-03. http://www.webindia123.com/arunachal/index.htm. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Arunachal Pradesh |

- Official website of the Government of Arunachal Pradesh

- Tourism in Arunachal Pradesh

- Arunachal News

- Inventory of Conflict and Environment (ICE), Arunachal Pradesh Territorial Dispute between India and China

|  | |||

| Assam | Nagaland |

| [show]Territorial disputes in East, South, and Southeast Asia |

|---|

| ||

| |||

SAARC

ReplyDelete